|

| April 07, 2020 | Volume 16 Issue 13 |

Designfax weekly eMagazine

Archives

Partners

Manufacturing Center

Product Spotlight

Modern Applications News

Metalworking Ideas For

Today's Job Shops

Tooling and Production

Strategies for large

metalworking plants

50 Years Ago: Apollo 13 and German measles -- NASA makes a last-minute change in plans

Left: Original Apollo 13 crew (left to right) Haise, Lovell, and Mattingly pose in front of their Saturn V rocket. Right: The Apollo 13 Saturn V on the eve of the launch.

By John Uri, NASA Johnson Space Center

The last few days before launch, Apollo crews typically finished up any last-minute training and also found time to get a little rest before the big day. Not so much with Apollo 13, the seventh crewed mission in the Apollo space program and the third meant to land on the Moon, scheduled to lift off on April 11, 1970.

As the prime crew of Commander James A. Lovell, Command Module Pilot (CMP) Thomas K. "Ken" Mattingly, and Lunar Module Pilot (LMP) Fred W. Haise and back-ups John W. Young, John L. "Jack" Swigert, and Charles M. Duke finished training, one astronaut's illness exposed the rest to an infectious disease resulting in an unprecedented change of crewmembers two days before launch.

Left: Haise (left) and Lovell during EVA training at KSC. Right: Duke (at left) and Young training for a lunar surface EVA.

Meanwhile, at Kennedy Space Center (KSC), on April 5 engineers began the extended countdown for the launch of Apollo 13, with the terminal countdown beginning April 10, preparing the Saturn V rocket and the Apollo spacecraft for the launch and trip to the Moon. Initial steps included loading kerosene fuel into the rocket's first stage and activating the Command and Service Module to begin the checkout of the spacecraft's systems.

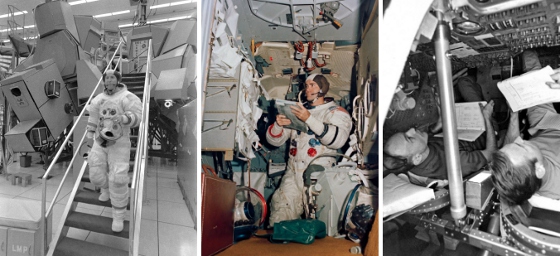

Left: Lovell descending the stairs from the LM simulator at KSC. Middle: Haise inside the LM simulator at KSC. Right: Mattingly (left) and Lovell inside the CM simulator at KSC.

After participating in the Countdown Demonstration Test (CDDT) on March 26, the astronauts resumed their training in the final two weeks before launch. Lovell, Haise, Young, and Duke finished their final training for the lunar surface Extra-Vehicular Activities (EVAs), Young completed his last training flights in the Lunar Landing Training Vehicle (LLTV), and all spent time in the Command Module (CM) and Lunar Module (LM) simulators and reviewing procedures and the overall flight plan. They also maintained their flying skills during flights aboard T-38 Talon jets. The orderly sequence of events was disturbed when Duke fell ill on Sunday April 5, just six days before the planned liftoff.

Three weeks before the planned April 11 liftoff, back-up LMP Duke and his family spent time with friends whose 3-year-old son came down with German measles, also known as rubella, the following week. Because Duke didn't have German measles as a kid, he lacked immunity against the rubella virus and came down with the disease.

Left: Lovell preparing for a training flight in a T-38. Middle: Haise preparing for a training flight in a T-38. Right: Mattingly (left) and Swigert share a lighthearted moment during training.

Duke had trained together and attended meetings with the other five crewmembers up until Friday April 3, while he was still contagious. During the crewmembers' L-5 day physical exams on Monday April 6, the flight surgeon collected blood samples and analyzed them to see if any of the astronauts had antibodies against rubella, although none except Duke exhibited any symptoms. The test results came back two days later with good news for Lovell and Haise, who had immunity probably from childhood exposures, but Mattingly did not.

Young and Swigert on the back-up crew were also immune. Dr. Charles A. Berry, Director of Medical Research and Operations at the Manned Spacecraft Center, now the Johnson Space Center in Houston, was concerned that if Mattingly were to come down with German measles, given the virus' incubation period it would likely be around the time they were in lunar orbit, possibly while he was alone in the CM. Symptoms such as fever, rash, and headache could interfere with his ability to perform intricate maneuvers to rendezvous with Lovell and Haise in the LM as they returned from the Moon.

Apollo program managers now faced a dilemma. No one wanted a sick astronaut during a critical phase of the mission.

Left: Management meeting at KSC on April 10 during which the decision was made to swap Swigert for Mattingly. Right: Press conference on April 10 to announce the crew swap decision.

One option was to delay the flight by 28 days to the next launch window in May 1970 that allowed a landing at the same Fra Mauro site with the same lighting conditions, but that was a costly proposition. Flying the entire back-up crew was not an option since Duke would still be symptomatic at launch time.

The only solution that made sense was to ground Mattingly and fly Swigert in his place. The back-up crew typically trains to be ready to fly the mission until about one month before launch, when the prime crew has almost exclusive access to the spacecraft simulators. While managers considered Swigert fully trained, he might have been a little rusty, so he began an intensive last-minute refresher training program on CM systems.

Left: Preflight meeting to discuss the crew change with (left to right) Slayton, Lovell, Mattingly, and Swigert. Right: The new Apollo 13 crew of (left to right) Swigert, Lovell, and Haise.

Fortunately, over the past few years, Swigert had developed the CM malfunction procedures, so he knew that spacecraft's systems probably better than any other astronaut. His proficiency satisfied managers that he could operate the spacecraft with no issues.

Another concern raised was that Swigert hadn't trained directly with Lovell and Haise and would the three form a cohesive crew. During several simulator runs, the three proved they could precisely execute intricate maneuvers as a team. Chief of Flight Operations Donald K. "Deke" Slayton agreed that Swigert was a proficient and well-integrated member of the crew and that the safest course of action was to ground Mattingly and fly Swigert in his place. During a press conference on April 10, the day before liftoff, Thomas O. Paine, NASA Administrator, announced the decision.

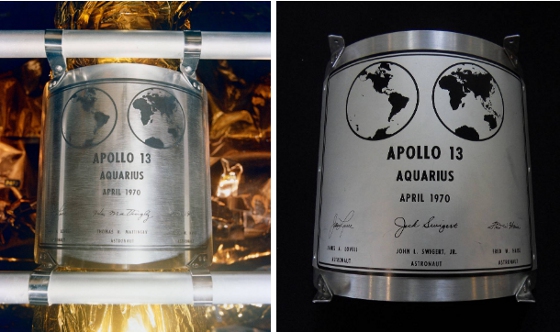

Left: Original plaque bearing Mattingly's signature mounted on the LM landing leg strut. Right: The replacement plaque bearing Swigert's signature.

Engineers at the launch pad had one more unplanned and somewhat complicated task to accomplish. The plaque that they had affixed to the LM's landing strut to commemorate the Apollo 13 lunar landing bore Mattingly's signature. With Swigert taking his place, workers quickly manufactured a new plaque with the new CMP's signature and flew it to KSC. Engineers working in very tight quarters inside the Spacecraft LM Adaptor placed the new plaque over the old one within a day of launch.

Published April 2020

Rate this article

View our terms of use and privacy policy